The Natural History Museum's new North Campus gardens have created an oasis in the midst of urban Los Angeles. (C) 2012 Ryan Miller/Capture Imaging; used with permission of NHM.

Location

Los Angeles, CA

Owner

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Architect

CO Architects

Landscape Architect

Mia Lehrer + Associates

Construction Manager / Owner's Rep

Cordell Corporation

Project Size

410,000 SF

ViewParadise Found: An Unexpected Eden at L.A.’s Natural History Museum

MATT Construction has just completed a key phase in the transformation of Los Angeles’ Natural History Museum. In preparation for its centennial, the Natural History Museum transformed the mostly paved property on its north side into a naturalistic garden that brings the museum experience to the very boundaries of its property. Eager visitors will find immediate entry to the garden, right next to public parking, the bus stop and brand-new Metrorail stop. Stepping through this portal, one is instantly immersed in the museum’s power and mission “to inspire wonder, discovery and responsibility for the natural and cultural worlds.”

For decades, most of the museum’s “North Campus” was consumed by two surface-level parking lots flanking an austere and inconveniently located entrance that rendered the museum literally and figuratively remote. Working with MATT Construction, Cordell Corporation, CO Architects, and landscape architects Mia Lehrer + Associates, the museum has completely reconfigured this space as an educational Eden.

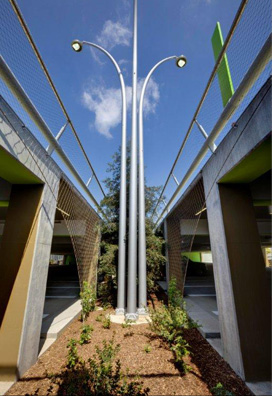

Oddly, the first new feature of the garden was a parking structure. Even odder, the structure manages to blend in with the garden. Lurking in North Campus’s southwest quadrant, the two level structure—one below and one at grade—is painted in earthy colors. Young redwoods and other trees planted on the lower level poke up through a narrow opening down the middle of the top deck. Vines and trees along the garden’s perimeter fence and the diversionary iconic “Dueling Dinosaurs” sculpture make the parking structure disappear from view.

Cruising down the structure’s gentle slope to the below-grade level, one finds the surrounding gardens have moved in. Planter beds have been installed along the long north and south sides, and within the structure itself. In fact, over 50 types of plant were used in the parking structure alone.

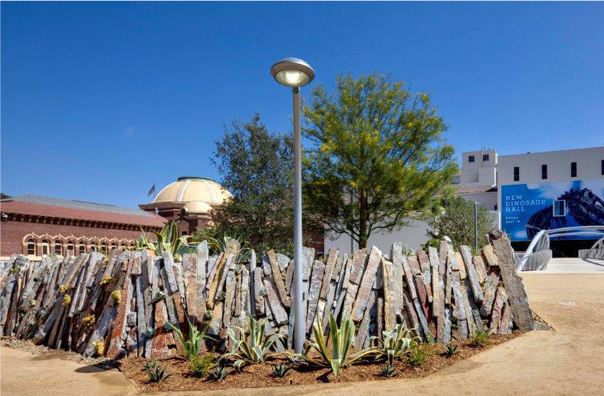

One travels to the surface via the “Transition Garden” alongside plantings both beautiful and beautifully adapted to the dry local climate. The garden that awaits at the top is, literally and figuratively, on another plane altogether. Huge stones, used to provide architecture, direction and multi-functional structures, are obviously not native to their current location. They evoke images of paleontologists at work, perhaps making discoveries displayed right here at this very museum. Nearly vertical slices of rock have been assembled into strikingly beautiful walls that buttress embankments and form raised beds planted with butterfly- and bird-attracting native plants. Each piece is a few degrees off vertical; no piece is really parallel to another, and gaps are filled with smaller stones or planted with succulents. This “Living Wall” has a slightly random, even chaotic look, as though it had been created by nature itself. The wall was conceived by MLA’s Michelle Sullivan, who chose to build it with “Pritchard Flagstone,” a richly colored sedimentary rock from Montana. Ultimately, the garden would absorb 3.2 million pounds of it.

© RMA Photography

Winding pathways invite visitors to continue wandering the garden at street level; descend a zigzag ramp of paths and planted embankments to a multi-purpose outdoor space called the “Strampitheater” (Stairway + Ramp + Amphitheater); or travel up and across a cantilevered bridge into the museum. Soon, the 60 ft tall Otis Booth Foundation Pavilion will be built out from the building onto the bridge, bringing the museum still further into its landscape and offering, through frameless glass walls, a sensational glimpse of an enormous fin whale skeleton suspended inside. To enhance the visual and physical flow linking interior to exterior, the glass pavilion extends below the bridge to the Strampitheater.

Honeycombed with forested paths that rise and fall over sculpted topography, studded with planters, arbors and water features, alive with birds and butterflies: the 3½ acre space seems larger than ever, yet at the same time much more intimate and human in scale. We can freely wander this growing urban oasis, amongst the sights and smells of exuberant flowering shrubs, banks of native perennials and outcrops of ground cover, enjoying the sounds of birdsong and skittering lizards. And whether or not we choose to enter the museum, the garden’s pathways and those unforgettable walls of broken rock from dinosaur time will draw us, finally, back to the paradoxical parking structure, where we began our visit.